I remain a believer in lower interest rates. I remain of the mind that deflation is a much bigger risk than either inflation or the dollar (which is a correlated risk anyway). Still, today's move had a lot to do with month-end rebalancing. The duration of the Barclay's Aggregate has risen from 3.73 on 3/31, to 3.96 on 4/30 and now to 4.33, all on MBS extension. The MBS portion of the Agg has moved in duration from 1.54 on 3/31 to 2.22 on 4/30 to 3.16 now.

So unless rates follow through on Monday, its debatable whether this rally is real. Again, I think the thesis is in tact, but I don't know whether the market believes it or not.

Month-end buying was also highly evident in the corporate market. I came in to do some buying myself and found offerings were like pulling teeth. Since I'm not married to month-end reporting like a lot of people, I decided to roll the dice and see what the market felt like on Monday.

And the stock market? I've seen some month-end window-dressing rallies, but today took the cake.

Friday, May 29, 2009

Treasuries: Have you ever heard the tragedy of Darth Plagueis the Wise?

Posted by

Accrued Interest

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: MBS, Treasuries

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

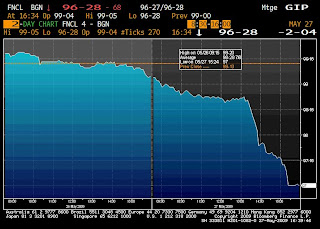

Yeah but this time I've got the money!

It was shades of 2002, only in reverse today. Mortgage servicers sold intermediate/long rates, which drove rates higher, which brought out more mortgage hedge sellers. Now we are set with some very basic problems.

Not good. Fundamentals in the housing market are weak enough without having affordability take a turn for the worse.

Taking a longer-term look at the mortgage current coupon, we see its still a good bit below the pre-conservatorship levels. Still, worrisome.

Interestingly, the Fannie Mae 4% MBS fell two points today, about the same price action as the long bond! There are no natural buyers of 4% and 4.5% coupons. They are a trap, as I've discussed before, all downside and no upside. Someday I expect this bond will trade at $91. And your upside is... collecting a 4% coupon? For probably 10 years? Where do I sign up!?!?!

Where does this leave us? With a bunch of problems I'm afraid. The massive decrease in money velocity has left us with a Alderaan-sized hole in the money supply. The Fed has already lowered the funds target to zero, so the only way to get more money into the system is to print it. Plain and simple.

The most efficient means to get printed money out into the world is to buy Treasury bonds. Not only does this put cash into the economy, but it also should lower borrowing yields and thus increase velocity.

When the Treasury buying program was announced, it was assumed that the Fed had some ceiling on Treasury yields in mind. This was a logical conclusion, since classically the Fed operates with a target, and buys or sells Fed Funds to meet that target. Why not do the same with the Treasury market? Target the 10-year at 3%?

But 3% came and went. 3.25% came and went. 3.5% came and went. The market kept waiting for the Fed to increase its purchases, but their purchase amounts have been remarkably consistent. Almost as though their only goal was to get money into the system, and they didn't really care about where Treasury bonds actually traded.

Helicopter Ben is trying to do just that. Print money and pass it out. He's just using the Treasury market as his helicopter. He's not actually trying to push yields lower.

And what about Asia? What about the U.S.'s AAA credit rating? Is the dollar about to plummet and foreign investors run away like Han Solo from Stormtroopers? I can't say there is zero risk of this, but think about it. Doesn't the negative outlook on the U.K.'s credit rating strengthen the position of the U.S. in terms of foreign buyers? If China cares about credit ratings (which traders I've talked to say they do), then doesn't S&P's actions take away one of China's main alternatives to the dollar?

I think foreign diversification of reserves is a reality. The dollar's dominant role in international commerce is fading, but it will be a slow fade. Many are expecting a Death Star like explosion of the dollar. Think of it more like Palpatine's rise. Slow and insidious over the course of many years.

Complicating all this is a very real risk that further Fed purchases of Treasuries will look like a monetization of our debt. I don't think that's the goal, but I can see how Asian buyers, especially outside of China, would come to that conclusion. Richard Fisher of the Dallas Fed has expressed exactly these concerns.

So I don't know what the Fed's next move is, but if interest rates stay where they are, those green shoots are going to turn to yellow. They need more water to start growing.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

9

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, May 21, 2009

Bill Gross: Do you trust him?

No... but he's got no love for the Empire, I can tell you that.

This morning, S&P put the AAA rating of the United Kingdom on negative outlook. Generally when S&P puts a negative outlook, it merely means they leaning toward a downgrade without any particular urgency. In this case, S&P says they need to see some progress made by an incoming British government on their burgeoning debt.

Since the U.K. is generally seen as the third most stable (U.S., Germany) of the big western economies, its not a big leap to say that the U.S. could be next. Its a perfectly legitimate concern. S&P mentions their concern that British debt could rise to 83% of GDP by 2013. In the U.S., its already 80%!

What would happen if the U.S. lost its AAA? Very hard to say. Foreign investors would still have the problem of finding someplace to put their money. I'd be surprised if the U.S. would lose its AAA rating, but say, France and Germany hold on to their ratings. Japan is already AA. It might result in a revision of how foreigners view ratings in general.

In other news, how is General Electric AA+ and stable if the U.K. needs to be downgraded? How is Assured Guaranty still AAA and stable?

Enter Bill Gross, always eager to talk his position. He stokes the fire by saying that the Treasury market is selling off due to ratings fears. Maybe. Indeed, I've heard that Asia is selling today. But always remember, when Bill Gross talks, he is always always always talking from position. So I'm assuming Gross is short Treasuries and today is adding.

I don't think really think the whole ratings thing makes sense to explain the Treasury sell-off. Here is the intra-day on Treasuries. S&P comes out with their report on the U.K. at 4:20 AM.

Treasuries are actually higher all during the Asian and European sessions, and its only once the U.S. session really gets going that the bond market sells off.

A better explanation is the continued belief that the Fed is defending some level on Treasuries. Admittedly, I thought they would, but the evidence is clear that they aren't. Here are the Fed's Treasury purchases since the program began:

Traders keep hoping the Fed will increase their POMO buys, whereas this chart clearly shows they keeping to the $7-8 billion range in the belly and about $3 billion on the long end. Their reluctance to increase purchases shows they either have no particular target or their target is much higher than where we are.

No sense in getting in the way of the Treasury negative momentum here. I'm probably not a buyer until 3.60%.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

10

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: credit ratings, Quantitative Easing, Treasuries

Treasuries and Stocks: If he could be turned...

Interesting to watch the Treasury market turn weaker today even as losses in stocks accelerate. I've been feeling for a while that the classic negative correlation between Treasury and stock prices will break down, at least on a day-by-day basis.

1) Any significant rise in Treasury prices will force consumer borrowing rates higher. There isn't much room for further spread tightening, especially in mortgages. So higher Treasuries probably means lower stocks.

2) Foreign buying is critical if Treasury yields are to remain low. Foreigners are more likely to buy when the dollar looks stable. The dollar is more likely to be stable if the economic picture is decent, and thus stocks advancing.

3) The stock market would probably welcome additional quantitative easing from the Fed. Based on yesterday's minutes, I expect any additional QE to be aimed squarely at the Treasury market. So Treasuries and stocks would both rally.

For what its worth, yesterday's minutes also indicated that the Fed doesn't have any particular 10-year yield in mind to defend. Or at least, if they do, that number is much higher than where we are. If the Fed cared about 3% or even 3.25%, the talk of expanding QE would have been more urgent.

Could you argue that allowing the 10-year to move from 2.50% to 3.25% is a de facto tightening of monetary policy? Maybe not, because most non-Treasury borrowing rates are lower today than 2 months ago, and thus you can't claim that credit availability has declined. However, I certainly think if they allow the 10-year to move much past 3.25%, they you will start seeing yields away from Treasuries back up as well. That will indicate tighter policy, which would be bearish for the economy.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Quantitative Easing, Treasuries

Friday, May 15, 2009

Municipals and Chrysler: What happens to one will affect the other

I've been notably absent in expressing my outrage over how the Obama Administration treated Chrysler's secured debt holders. Let it be known I'm sufficiently outraged on the inside, but resigned on the outside. We should all take it as a lesson: you simply never know what the government might do. The more they tighten their grip, the less I want to invest in any company which has taken government money. Especially in the investment-grade bond market, where, generally speaking, the potential for appreciation is limited.

This brings us to the municipal bond market. In Berkshire Hathaway's 2008 letter to shareholders, Warren Buffett had this to say about the municipal insurance business (the section starts on page 13 if you want the total context). Hat tip to downwithcapitalism who, despite his evil galatic moniker inspired this post.

"A universe of tax-exempts fully covered by insurance would be certain to have a somewhat different loss experience from a group of uninsured, but otherwise similar bonds, the only question being how different.

To understand why, let’s go back to 1975 when New York City was on the edge of bankruptcy. At the time its bonds – virtually all uninsured – were heavily held by the city’s wealthier residents as well as by New York banks and other institutions. These local bondholders deeply desired to solve the city’s fiscal problems. So before long, concessions and cooperation from a host of involved constituencies produced a solution. Without one, it was apparent to all that New York’s citizens and businesses would have experienced widespread and severe financial losses from their bond holdings.

Now, imagine that all of the city’s bonds had instead been insured by Berkshire. Would similar belttightening, tax increases, labor concessions, etc. have been forthcoming? Of course not. At a minimum, Berkshire would have been asked to “share” in the required sacrifices. And, considering our deep pockets, the required contribution would most certainly have been substantial."

At the time the letter was made public, back in February, I thought it was mostly just Buffett's way of 1) Making sure he could keep charging exorbitant sums for muni reinsurance, and 2) Temporing shareholder's expectations for the muni insurance sector. After all, there is no record of insured bonds defaulting at a higher rate than uninsured bonds, controlling for all other factors. And the type of behavior Buffett warned of hasn't been evident with Jefferson County, where the overwhelming majority of outstanding bonds are insured. In fact, I'd bet that the insurers have better lawyers and other workout specialists at their disposal compared to what any ad-hoc group of bond holders could put together.

In addition, notice Buffett says "imagine all the city's bonds had been insured... by Berkshire." This isn't the case in reality. Any large issuer is going to have a mixture of insured bonds with various monolines. Given the state of XLCA, CIFG, FGIC, and Ambac, I'd say that de facto, most issuers have a fair number of bonds that are now uninsured. Certainly its fair to say that the local investors, who Buffett argues prevented politicians from ravaging bondholder rights, would suffer a large market value decline if any issuer fell into default, even if the bonds were insured, since all insurers are seen as weak.

Still, we've seen the precedent set by Chrysler. I've argued many times before that state and local governments can't choose to pay teachers and not bond holders. But can we universally assume this will remain the case? As readers undoubtedly have read numerous times, Chrysler's "secured" bondholders suddenly found themselves unsecured by Fiat (pun intended). Why? Because it was politically expedient.

Couldn't the same thing happen in a municipal bankruptcy? Especially if the Federal government gets involved? Absolutely it could.

I don't see this happening with some local school district someplace. Take Vallejo or Jefferson County, both of which are going on right now. So far it looks like the courts are playing a lesser role in both cases, with politicians and debt/swap holders negotiating directly. These are the kinds of bankruptcies I expect out of munis in the next few years.

But what if a really large issuer, like the city of Detroit, were to enter Chapter 9. Then what if the Federal government stepped in to provide some sort of bridge financing. Then suddenly the Treasury gets to dictate terms, and Obama has shown he's not going to make the unions bear the same burden as bond holders. I'd argue that the public employees unions are more powerful than the UAW!

If that happened, then immediately local governments would see bankruptcy as an expedient solution, solving structural deficits by punishing bondholders.

Ultimately, this would be an incredibly foolish course of action. Consider the consequences: the municipal bond market would shut down, with only the strongest issuers able to come to market, and maybe not even those issuers. Suddenly the Federal government would become the only source of municipal funding. The U.S. would turn into a true Federal state.

So I sure hope this isn't the direction we head. The long-term consequences would be devastating. You'd like to think the Administration has the sense to consider the long-term impact of their decisions, and wouldn't kill municipal bond holders. But then that's what I said about letting Lehman go bankrupt...

Posted by

Accrued Interest

7

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: monolines, municipals

Thursday, May 14, 2009

Corporates: All craft retreat!

Corporate spreads weak again today. Heard that J.P. Morgan's new 5-year was 20bps wider than issue, American Express 10ish weaker on the break, InBev weaker again. The new Simon Property is 25 weaker today.

On the positive side, it sounds like the new Wal*Mart bonds did OK, came at 130, now 10ish tighter.

Worth noting, from a macro perspective, new issue buyers are a fickle bunch. If they have bad experiences with one sector or name, the tend to stay away in the future. So its important that these new financial issues perform well or it may become difficult for future issuers. So far, even though AXP and JPM didn't do that great, a lot of the other issues are still mildly tighter (BAC, GECC), but its worth watching.

Weakness in the credit market makes you scratch your head at how well stocks are doing today. Smells like options expiry BS to me. I covered part of my S&P 500 short yesterday, added a short of JNK. Might add back to my S&P short if we rise any more. I like 875 as a target.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

6

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Corporates

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Leveraged ETF Math: This may smell bad, kid

The other day I was asked why I'm short SSO as opposed to just long SDS. The answer is that there is natural drag on leveraged ETF prices. Part of this is due to the decay factor in futures pricing. But the bigger factor is just the math of multiplication and time linked returns.

Bear in mind these are my personal investments, not anything I'm doing professionally.

OK, let's use a product like SSO, which is the 2x leveraged S&P 500. The way its supposed to work is that every day, you get 2x whatever percentage return is on the S&P 500. On Monday, SSO closed at $25.73. If the S&P 500 were to finish up 1% today, SSO should be up 2%, or $0.51 to $26.24. If its then down 1% the next day, SSO should be down 2%, or -$0.52 to $25.72.

Over time, the math of total return (in percentage) looks like this (just in general, not of these ETF's specifically):

(1 + X0) * (1 + X1) * (1 + X2) ... (1 + Xn) -1

Where X is day n's return.

Now you'll notice that if we get the exact same percentage return, but in opposite directions, on two separate days, it doesn't mean your total return will be zero. For example, say you lose 1% on day 1, but gain 1% on day 2.

(1 - 0.01) * (1+ 0.01) - 1 = -0.0001, or -1bps.

The more severe the return, the more severe the result. Say its -10% and +10%. The result would be ...

(1 - 0.1) * (1 + 0.1) - 1 = -0.01, or -1%.

It doesn't matter what order these occur in, because multiplication is commutative.

(1 + 0.1) * (1 - 0.1) - 1 = -0.01, or -1%.

It would therefore seem like there is a natural negative drift in security prices. But in the normal world, we assume security prices aren't dependent on previous percentage gains, but on some fundamental valuation. For example, if I buy a bond at $100 but it subsequently has some credit problem that results in it falling to $90, I will have lost 10%. But if the credit problem is resolved and it gets back to par, I realize a 11% gain. I'm not limited to getting back the opposite of what I lost.

But the multiplication factor of ETFs sort of mess with this. Let's say the S&P 500 drops by 2% on day 1, then rises by 2.0408% on day 2 (which puts you back to where you started), and repeats this pattern for 6 days.

Now let's say you own the double long ETF, and we'll assume the ETF works as its supposed to. On day 1, you'd lose 4% (-2% * 2) and on day 2 you'd make 4.0816% (2.0408% * 2). But do the math...

(1 - 0.04) * (1 + 0.040816) * (1 - 0.04) * (1 + 0.040816) * (1 - 0.04) * (1 + 0.040816) - 1 = -0.24%

Why? Think about the pay back formula, i.e., percentage return you need in period 2 to go back to zero given a loss in period 1. Its ...

1 / (1+x) - 1

Now if the S&P return was x, then the ETF return is going to be 2x. But notice that...

2 [1 / (1+x) -1] <> [1 / (1+2x) -1]

See? In fact, the left equation is always going to be larger than the right equation if x is negative, and always smaller than if x is positive.

Now I can't say there is a real arbitrage here, because if the market moves higher or lower decisively, that will dominate all these pretty equations. But if you are short-term trading, it seems to me you're better off shorting the opposite ETF than going long. So I'm making a bearish play by going short SSO as opposed to owning SDS.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

21

comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, May 11, 2009

Corporates: I'll never turn to the wide side!

Corporate spreads are weaker this morning, finally. I've been feeling like a pull back is long over-due in corps. Beyond the general feeling, two interesting notes on today's movement.

1) Recent new issue Dow Chemical is getting trounced. Dow's 10-year (8.55 5/15/19) was priced on 5/7 at a spread of 525bps over the 10-year. Now the bid is +600. Most recent new deals have moved quickly tighter, anywhere from 15-50bps almost immediately.

2) Other new issues producing mediocre results. Bank of New York, BB&T, Morgan Stanley, all basically at new issue levels. Again, most new issues have moved substantially tighter on the break. For what its worth, GE and Bank of America's deals are doing a little better, maybe 20ish tighter.

3) Today's InBev deal isn't going gang-busters either. Initially the price talk was "Low 300's" and "Mid 300's" for a 5-year and 10-year tranche. Recently when you've heard "Low 300's." that meant it would actually be +290. When you heard "Mid 300's" that would actually be +325.

The deal actually will come at +337.5 and +375 respectively. So they actually had to widen this thing to get it sold. I don't think its some kind of teetotaller conspiracy. I think the rally in corporate bonds is exhausted and its time to set up for a pull back.

Remember that when every one heads for the exits in corporate bonds, the Street won't be taking on massive inventory to take customers out of their positions. So the pull back could be more violent than the economic outlook would indicate.

Among other new issuers today was Microsoft, who sold bonds with a Micro spread of 105bps. Agencies were wider than that less than 6-months ago! Also Simon Property with their second offering this year, the other on 3/20. Worth noting that their March deal was sold at $97.5, now over $110. Coupon is going to be in the "high 7's" as opposed to the 11% yield on the previous issue.

For those who care, I've recently put on a decent short on the S&P (shorted SSO mostly) expecting a pull back there. It makes me a little nervous that this seems like such a popular view, though.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

7

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Corporates

Tuesday, May 05, 2009

Inflation: Not this ship, sister

Alright so the Fed isn't going to defend the 10yr at 3%, and in fact appears to be targeting the belly of the yeild curve. That doesn't change the fundamental problem of deflation. Near term, based entirely on technicals, I've made a small short play in Treasuries. But I'm really just looking for a new entry on the long-side.

Almost exactly 2-years ago, I made my now famous (in my own mind) analogy of inflation to a Monopoly game. Basically my point was inflation wasn't about the price of any given property (or good) but the price of all the properties. Allowing any given good (at the time it was energy) to rise isn't, in and of itself, inflation.Now there is fear that the Fed and Treasury's activities, especially the Fed's recent panache for "crediting bank reserves" (which means printing money). Here is the chart for M1 and M2 up 14% and 9% respectively in the last year.

Back to my Monopoly analogy. We might think of the M's as the actual multi-colored cash that each player has. As I demonstrated two years ago, an increase in cash available should cause the price level to rise, but only if you hold the savings rate constant.

Speaking more technically, you could say that an increase monetary base would have some multiplied impact on transactable money. In your textbook from college, this only involved banks and their willingness to lend. Actually, most often text books assume banks want to lend as much as they are legally allowed, which isn't the case right now. But I digress.

The securitization market makes this all much more complicated. The supply of loanable funds isn't just a function of cash in the banking system, but also cash invested in the shadow banking system. Right now net new issuance in ABS (meaning new issuance less principal being returned in old issues) is negative, meaning supply of funds from the shadow banking system is contracting.

This contraction of funds doesn't show up anywhere in the Ms, at least not directly, but obviously it matters in terms of consumers ability to buy goods. And it isn't just about availability of credit, which had everything to do with liquidity. Its about demand for credit also. Consumers want to save, they don't want to borrow right now. The following chart of household liabilities shows consumers actually decreased their total liabilities in 2008, the first year-over-year outright decline since the Federal Reserve began keeping the data in 1952.

Consumers are like a Monopoly player who has mortgaged all his properties. Passing GO doesn't cause him to buy more houses, it causes him to unmortgage his properties! That isn't inflation!

Getting back to consumers, it isn't clear to me that consumers are actually running out of money. Check this chart of the Household Financial Obligation Ratio, basically a debt service coverage ratio for consumers.

So consumers might not have to repay debt all at once, which is nice. It means a second-half recovery of sorts remains in play. But the large losses in assets coupled with out-sized debt ratios are going to cause consumers to keep saving at an elevated level. Check out liabilities as a percentage of disposable income.

This isn't a perfect ratio, since liabilities is a stock and income is a flow. But with declining asset values (both homes and financial assets), means that consumers are actually going to have to rely on incomes to pay debt service. Or for that matter to qualify for loans. So I'd think this ratio moves back toward 100%. That implies $3.6 trillion. TRILLION. It will be repaid over time to be sure, but it will remain a continual drag on consumer spending levels.

So keep this in mind when you think about the size of Fed/Treasury programs. $3.6 trillion. Are we worried about $800 billion for the "Stimulus Package" or the $1 trillion revised TALF? Not in terms of inflation.

I'm looking forward to the day when I'm worried about inflation. It isn't today.

Posted by

Accrued Interest

23

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: inflation, TALF, Treasuries